'Expanded

Cinema' is the term coined by writer Gene Youngblood to describe the

group of filmmakers in the 1960s who shifted the boundaries of what

experimental film could be. They would transcend the flat, single

projection movie screen in favour of multi-sensory experiences and

unique viewing environments. Youngblood described their work as an

extension of “man's ongoing historical drive to manifest his

consciousness outside of his mind, in front of his eyes.” Likewise,

the content of many of these films eschewed traditional narrative in

favour of abstract thought, ruminations on the cosmos, the

subconscious, dreams and nightmares. It is with this is mind that I

approached this list, the idea of psychedelia as an expansion of

consciousness, through any means. I've chosen films that are easily

available to view, so more well-known films may be omitted. Some of

the films below prefigure the idea of expanded cinema, but certainly

laid the foundations for the movement to come. It is by no means

intended to be an exhaustive list, more a primer that will hopefully

lead you on a path of psychedelic wonderment!

MARY

ELLEN BUTE – Synchronomy No. 2 (1935/36)

Mary

Ellen Bute was one of the first female experimental film makers, and

an exponent of “visual music”, the synchronisation of sound and

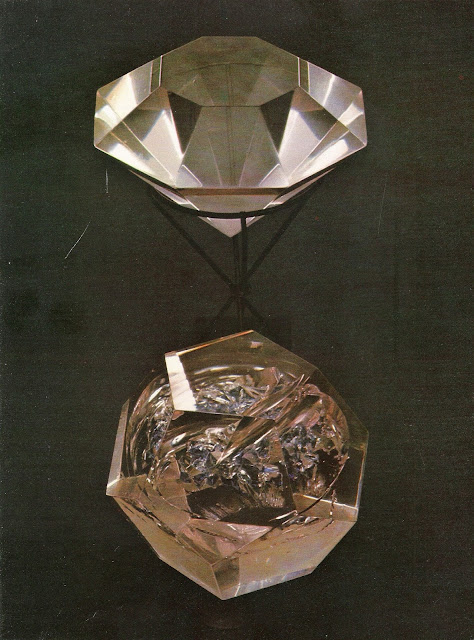

image in a startling and imaginative form. Created through light

refractions and lenses, Synchronomy

No. 2 urges

the viewer to imagine “seeing sound,” before soft abstract shapes

and shadows combine and rotate to the sounds of 'The Evening Star' by

Wagner. Futurist constructions meld into crystal facets, animated

blocks build staircases and gothic arches, a female form, disjointed

through a prism, slowly reveals itself as a statue of Venus. Neither

the image nor the music is defined as being more significant than the

other, rather the two converge in an organic manner and the effect is

mesmerising, almost dreamlike.

Bute's

work would go on to incorporate more complex shapes and movements,

eventually utilising the oscilloscope to consolidate her ideas of

combining sound and image. Her films were a huge

influence

on a generation of filmmakers, most significantly Norman Mclaren and

his playful visual symphonies of dancing lines and shapes.

HARRY

SMITH - Film #11: Mirror Animations (1957)

Harry

Smith's prolific work as an experimental animator is often eclipsed

by his other numerous creative endeavours, as painter, alchemist,

anthropologist and folk music archivist, yet this sprawling body of

work alone is enough to solidify his standing as some kind of

beat-era celluloid sorcerer. His own psychedelic experiences while

listening to music inspired him to attempt to capture, in a dynamic

form, the shapes and images his mind conjured up. The resulting films

combined mysticism, the occult, alchemy, dada and surrealism in

Smith's unique vision. They were created with a combination of

collage, painted film and multi-layered projections onto three-

dimensional constructions. The effect in #11:

Mirror Animations

is truly enchanting, with shapes and objects dancing around the

frame, choreographed to the music of Thelonius Monk (who

undrestandably nicknamed Smith “the magician”). Smith's visual

language is at once absurd and sublime, a mass of symbols fighting to

be deciphered. Any attempt at interpreting meaning is soon overcome

by a feeling of awe and pure wonder at the stream-of-consciousness

images. He's less the filmmaker, more the magic lantern showman,

orchestrating his own phantasmagoric visions to the amazement of

onlookers.

STAN BRAKHAGE –

Dog Star Man (1959-64)

Watching

a Stan Brakhage film is akin to experiencing life in it's entirety,

from overwhelming beauty to disorienting confusion and all points

between. Colours flicker and pulsate, shapes contrast and collide,

focus drifts from the semi-recognisable to the completely abstract.

Brakhage thought of film as a reflection of vision, not only the open

eye, but “closed-eye vision”, the abstract patterns and pulses of

colour one sees with eyes closed, visual memories, imaginations,

hallucinations and dreams. In addition to conventional camera use, he

employed a dazzling array of experimental techniques: painting,

scratching and bleaching the film; exposing objects and textures onto

the film before printing; and even growing mould onto the film

surface.

Dog

Star Man hits the viewer

with a barrage of images, the central repeating motif of a man

climbing a hill and cutting down a tree is distorted, refracted,

interspersed and overlaid with footage of solar winds, the moon and

stars, a beating heart and bloodstream. He shifts focus between the

telescopic and the microscopic, outer space and inner space, to

meditate on his own place in the cosmos.

JORDAN BELSON –

Samadhi (1967)

Jordan

Belson helped pioneer the concept of the psychedelic lightshow

through his role as visual coordinator of the Vortex

Concerts,

multi-projector film performances accompanying contemporary

electronic sounds and musique

concrète held

at the Morrison Planetarium in San Francsico during the late 50s.

Although initially inspired by his own psychedelic experiences,

Jordan Belson's films sought to capture something more transcendental

as he evolved as a filmmaker. As well as references to Eastern

mysticism (the mandala is a recurring symbol in his early work),

Belson's immersion in meditation is explored in Samadhi

(which

is Sanskrit for “that state of consciousness in which the

individual soul merges with the universal soul”). There is

something truly cosmic about Samadhi,

galaxies expand and dissipate, heavenly bodies shimmer and gaseous

forms swirl. We appear to travel to the heart of a star, as particles

fly past us and an intense glowing colour field fills the screen.

This otherworldly imagery is made all the more remarkable as it was

created using Belson's home-built contraption incorporating an old

X-ray machine, various rotating tables, lights, motors, lenses and

prisms, and filmed in real time. The music was also created by Belson

on electronic equipment and works in complete harmony with the

visuals, soundtracking the cosmic events we are witness to. The sound

is so integral to the imagery that Belson said of it, “you don't

know if you're seeing or hearing it.” Belson's work was a huge

influence on Stanley Kubrick and Douglas Trumbull when creating the

stargate sequence for “the ultimate trip”, 2001.

SCOTT BARTLETT –

OffOn (1968)

Released

the same year as 2001,

OffOn

by Scott Bartlett could be a spiritual cousin of Kubrick's sci-fi

vision. It's largely considered to be one of the first works to

combine film and video together, being filmed in monochrome, then

coloured by hand and processed using the emerging video technology of

the time. It begins with the close-up of an eyeball, over-saturated

with colour, which flickers and throbs to the sound of a human

heartbeat. Colours are polarised, images cross-pollinated using video

feedback as we are drawn further into the eye. Vibrations gather

around a growing force-field which expands and gives birth to a human

figure, dancing along to a mirrored version of itself. Bird

silhouettes swoop into the frame, encircling the disintegrating

dancer, who begins to break off into geometric segments revealing a

close-up female face. This metamorphosis continues, images fizzing

and degrading, decaying off into infinity until a final burst of

energy fades to nothingness. OffOn

is the perfect representation of film as an extension of human

consciousness, a celluloid journey through the eye to the centre of

the mind, fed through electronic circuits and cathode ray tubes, then

back into our retinas through the medium of light - a feedback loop

of human perception.

LAWRENCE JORDAN –

Orb (1973)

An

associate of Stan Brakhage, Lawrence Jordan spent a portion of his

early artistic career as an assistant to Joseph Cornell, and his

films seem to belong to the same tradition, almost like Cornell's

boxes opened up and brought to life in celluloid form. Jordan was a

pioneer of cut-out animation, collaging 19th

century engravings and Victoriana and bringing them to life with the

same kaleidoscopic wonder as a psychedelic light show, the

fantastical visions of Jules Verne skyrocketed into the psychedelic

age. Orb

takes us directly through the looking glass, following a balloon-like

object as it passes through fragmented Gustave

Doré

landscapes and architecture, flickering and transforming into the

sun, moon and stars, alchemic symbols and planets. The symbols are

repeated in rapid-fire colour overlays, taking us to increasingly

fantastical landscapes, until the orb of the title expands and

envelops the screen. This journey is less about specific place and

time, moreover a transformation between different dream-states, a

free-association of imagery Jordan described as “theatre of the

mind.”

YouTube Playlist:

Further Reading

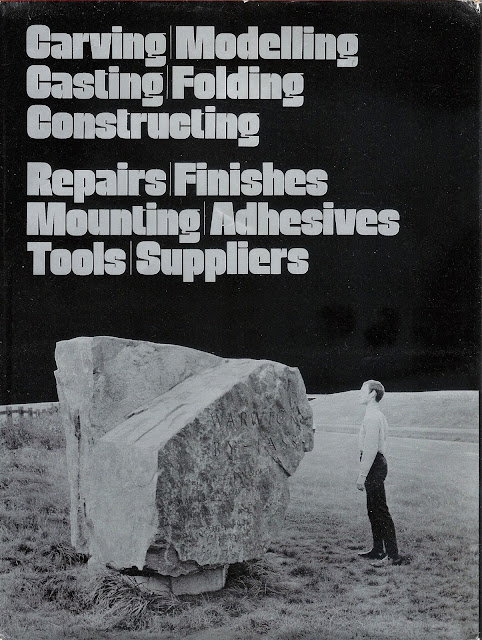

Expanded

Cinema – Gene

Youngblood, 1970, Studio Vista, SBN 289 70113 9

The

Underground Film –

Sheldon Reenan, 1967, Studio Vista, SBN 289 37061 2

https://expcinema.org/

- A great resource for experimental film, past and present.

http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/

- Film archive holding the work of Jordan Belson, Mary Ellen Bute and

Oskar Fischinger, amongst others.

http://www.ubu.com/film/

- An extensive archive of avant garde films, animations and

documentaries.

http://lawrencecjordan.com

– Personal site of Lawrence Jordan, with extensive biography and

filmography.

https://www.nfb.ca

– Online archive of the National Film Board of Canada, featuring

much of the work of Norman McLaren.